ART WORLD NEWS

Paintings by Arakawa Beguile at Gagosian in New York -ARTnews

[ad_1]

Installation view of “Diagrams for the Imagination” at Gagosian Gallery.

©ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION OF THE ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/PHOTO BY ROB MCKEEVER/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

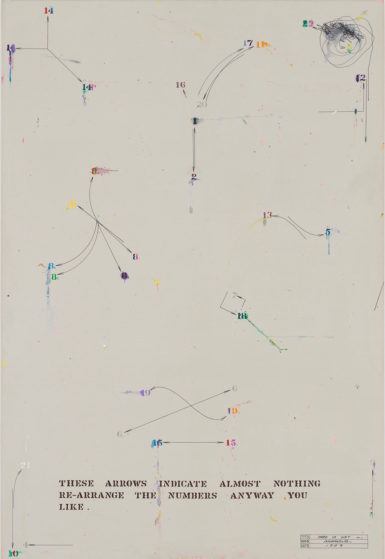

Hard or Soft No. 3, a painting in the Arakawa show “Diagrams for the Imagination” now at Gagosian Gallery in New York, teems with specs and information. Lines guide and point, like vectors. Numerals take up positions at the ends, signs of a system at work. All of the marks are measured and methodical, with significance waiting to be surmised.

But then, some words at the bottom state, “These arrows indicate almost nothing / Re-arrange the numbers anyway you like.”

Arakawa, Hard or Soft No. 3, 1969.

©ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION OF THE ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/PHOTO BY ROB MCKEEVER/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

Placing eyes squarely on a trail and then throwing them off in every which way was a specialty of Arakawa’s at the time he made the work. Hard or Soft No. 3 dates to 1969, a few years after the artist’s start as a painter and some two decades before he gave up the pursuit to focus instead—with his wife and close collaborator Madeline Gins—on architecture. In the time between, Arakawa sketched out a world on canvas that turned inward and outward by its own designs.

“These were diagrams of the mind and thinking, how to look at art, what art’s role is, how one deciphers it,” said Ealan Wingate, the Gagosian director who organized the show, which runs at the gallery’s Upper East Side location through April 13. (Gagosian began representing the late artist in 2017.)

The first such show in New York since an exhibition of Arakawa and Gins at the Guggenheim SoHo in 1994 (another, mounted last year at Columbia University, focused on their architecture), “Diagrams for the Imagination” follows the recent appearance of a curious Arakawa painting in the big tribute to the renowned dealer Virginia Dwan at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Arakawa’s Untitled (‘Stolen’) featured in that show, “Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971,” with a title that told part of its story.

When the painting was first shown by Dwan in New York in 1969—with text on the canvas reading “If possible steal any of these drawings including this sentence”—a group of students from Rutgers University conspired to thieve it, following what they took as instructions. When Arakawa learned of the stunt, he was irked at first but ultimately pleased. (“That a painting, and particularly a conceptual painting, should generate such passion is beautiful,” he’s quoted as having said in the Dwan exhibition catalogue.) He was so pleased, in fact, that he urged the students to donate the work to a museum—hence its current home in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

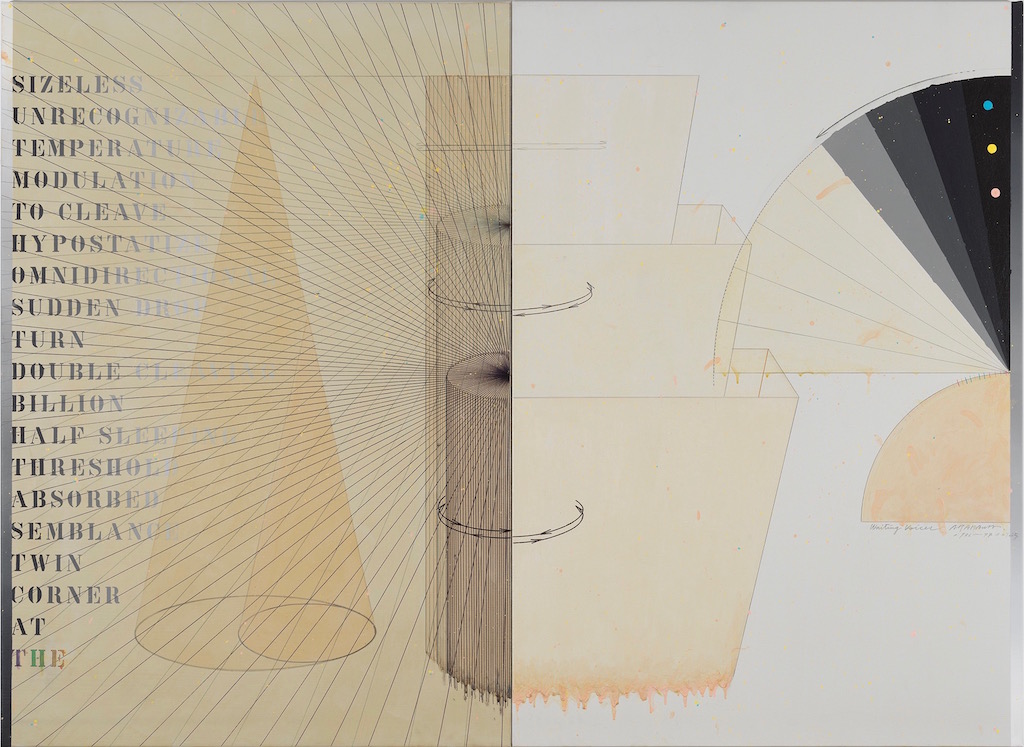

Arakawa, Waiting Voices, 1976-1977.

©ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION OF THE ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/PHOTO BY ROB MCKEEVER/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

That storied painting is not in the Gagosian show, but 23 others are—each with a sense of cerebral deliberation but without “the dryness we associate with so much conceptual work,” as Wingate said. The Signified or If (1973) is a would-be philosophical word painting—of the kind championed in Dwan’s early “language” shows featuring high-profile peers like On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Robert Morris, and Robert Smithson—with a stenciled message that takes a comic turn: “When ‘always and not’ signifies something ‘the signified or if’ belongs to the zero set!! Have we met before??”

Other works seem to hold out secret schematics for relationships between people and things that make sense up to the point when one might pause and try to articulate what that “sense” could possibly be. One half of A Couple (1966–67) is a sort of psychological blueprint of a room labeled with locations for a television, clothes, table, lamp, bed, heads, and so on; the other half removes the words and suggests a sense of something having happened between the couple who call the room home. (An open window letting in a sliver of yellow sun shows time having lapsed.)

“It’s a diagram of a diagram—it keeps on going,” said Wingate. “It’s a wonderful way of viewing the deconstruction of an interior or a tryst or a life together. It makes as much sense as you can bring to it.”

Arakawa’s paintings point toward a locus for understanding whose precise coordinates can prove elusive, much in the same way that his later architectural work with Gins courted contradiction and paradox under the aegis of their Reversible Destiny Foundation. Death could be bested, the artists theorized before meeting their own respective ends—Arakawa in 2010, Gins in 2014—and even if it couldn’t, there’s no reason not to at least consider the possibility.

Untitled (Voice Inoculation) installation view at Gagosian Gallery.

©ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION OF THE ESTATE OF MADELINE GINS/PHOTO BY ROB MCKEEVER/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

Untitled (Voice Inoculation)—a painting from 1964–65 with backward text and a skewed orientation around an axis that seems to invert the picture plane—appears somehow both highly technical and impish at once. “It’s playing with a different dimension,” Wingate said. “It’s a Dadaistic conundrum—it doesn’t go as far as Beckettian absurdity, but it hovers over the impossible.”

Arakawa—who was born in Japan and moved to America in 1961 (“There’s a fabled story that he gets to New York with $14 in his pocket and Marcel Duchamp’s phone number,” Wingate said)—expressed a liking for such states early on. As noted in a new catalogue published by Gagosian, the artist wrote, in a text titled My Plans, “What I want to paint is the condition that precedes the moment in which the imagination goes to work and produces mental representations.” In another text titled Notes on my paintings—What I am mistakenly looking for, he wrote, “The more precise a painting or a language (several languages: painting, color, shape, words, etc.) is, the less it exists as itself. But the more it can determine an area of meaning or an unnamable presence.”

A certain sense of uncertainty and confusion has followed Arakawa after death. A lawsuit filed last year against the Reversible Destiny Foundation and the estate of Madeline Gins took issue with ownership rights surrounding The Mechanism of Meaning, an 80-panel painting whose component parts have been a matter of controversy. And while the sprawling Mechanism of Meaning as a whole does not feature in the Gagosian show, a follow-up to the suit filed last week contends that some of the canvases in the exhibition might be “part of the Work that exist as paintings outside of the first and second editions.”

The multitude of ways that Arakawa’s work can be contemplated and then understood and misunderstood simultaneously points back to the arrows in Hard or Soft No. 3—arrows that “indicate almost nothing.” The sly presence of almost would appear to call for special attention—unless, of course, it does not.

In any case, the work seems to want to be read. “The provocation is to get to a diagrammatic point of view when looking at a work of art as something more than perceived decoration,” Wingate said. “We question our relationship, and it coerces us to engage.”

[ad_2]

Source link