ART WORLD NEWS

Art World Responds to Warren B. Kanders’s Resignation from Whitney Board -ARTnews

[ad_1]

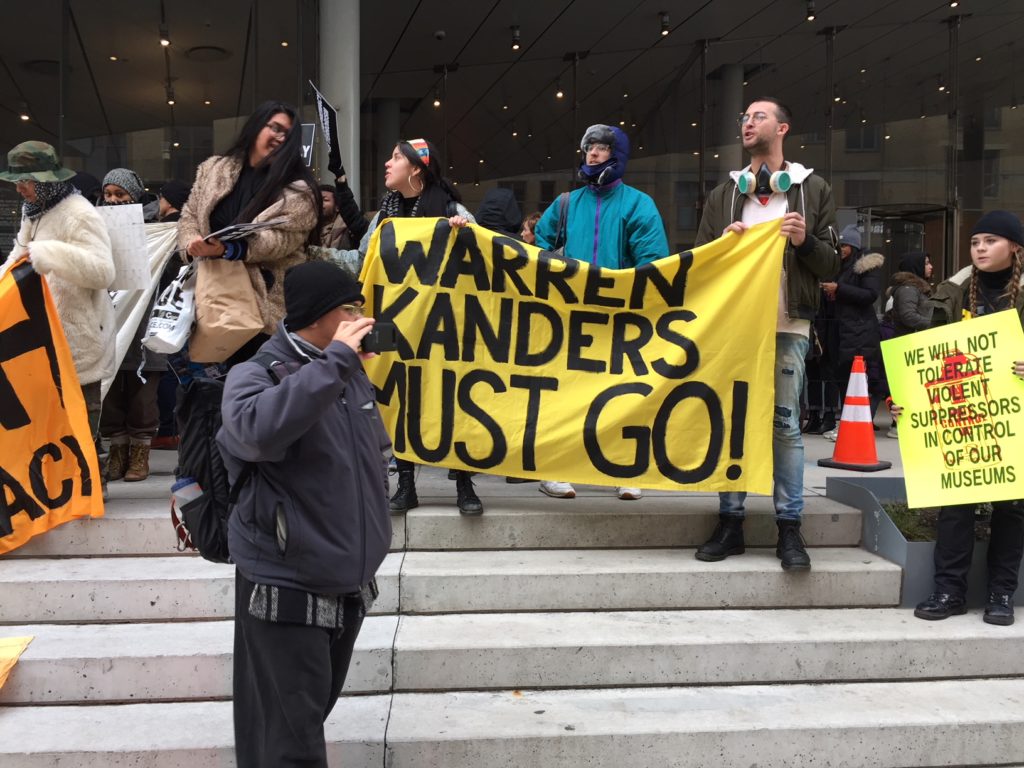

A Decolonize This Place protest at the Whitney Museum on December 9, 2018.

ALEX GREENBERGER/ARTNEWS

On Thursday, one of the most complicated and divisive controversies in the art world in recent years came to close, with Warren B. Kanders resigning from his position as vice chair of the board of the Whitney Museum in New York after months of protests about his ownership of Safariland, a defense-manufacturing company.

“The targeted campaign of attacks against me and my company that has been waged these past several months has threatened to undermine the important work of the Whitney,” Kanders wrote in a letter to the board. “I joined this board to help the museum prosper. I do not wish to play a role, however inadvertent, in its demise.”

Protesters had taken issue with Safariland’s production of tear-gas canisters that had been used against protestors around the world, including, most recently, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and his stake in Sierra Bullets, which sells high-velocity ammunitions that have allegedly been used against Palestinian civilian protesters by Israeli soldiers in Gaza.

“Mr. Kanders did what he should’ve done in the beginning,” curator Dan Cameron told ARTnews. “The situation had been untenable for quite a while, and the artists were sending increasingly urgent signals to that effect to the museum. It seemed that the museum was being unresponsive.”

With Kanders now out, artists, activists, and other art figures are wondering what comes next. Which patrons might now become the focus of protests? Will museums will rethink their board membership policies? And how will the answers to those questions affect the funding and operation of museums?

For many who spoke with ARTnews, Kanders’s resignation is a sign of the shifting balance between museum boards and their critics, with protesters scoring a clear victory. Cameron tied the Kanders situation to the ongoing criticism of Sackler family and other controversial arts funders. Asked how cultural institutions should adapt to the new climate, Cameron’s solution was simple: “Museums need to be circumspect about whom they invite onto their boards.”

Whitney Biennial artists responded to the news with a mix of relief and exhaustion. San Juan–based artist nibia pastrano santiago, who staged a performance as part of the exhibition at the museum in June, noted that Kanders’s resignation came hours after Ricardo Rosselló, Puerto Rico’s governor, said he would step down amid reports of corruption. Santiago was teargassed as part of the protests against Rosselló, possibly via the same canisters produced by Safariland. “With the resignation of Kanders, and also the resignation of Rosselló, it’s just the beginning of a new potential for dealing with funding and how to curate and what spaces can be made,” she told ARTnews in a phone interview. “It reminds me that the power of putting your body out there in protests has an effect.”

A protest held by Decolonize This Place held at the Whitney Museum on March 22, 2019.

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

The exact details of what led to Kanders’s departure are not yet known. It came after eight artists called on the museum to remove their works from the Whitney Biennial in a protest against his continued presence on the board.

Past Whitney Biennial participants have also been following the events and mulling what has transpired. Coco Fusco, who participated in the politically charged 1993 edition of the show, said that Kanders’s resignation marks a “watershed moment” for the art world. “The pressure has been mounting on museums to take a stand with regard to patronage from morally questionable sources,” she said in an email. “This is an issue that few have dared to touch during the art boom years of the early 2000s, even though just about everyone knows that the arts are awash in dirty money.

“Artists are regularly warned by their dealers and promoters not to bite the hand that feeds them,” Fusco continued, “and the justifications that arts professionals usually use for keeping quiet are pretty ridiculous. It will be very interesting to see how the profession responds in the longterm.”

Martha Rosler, who’s appeared in four Whitney Biennials, and whose work has long dealt with holding art institutions accountable for their connections to violence and conflict, drew connections between the Kanders protests and historical events, mentioning protests in the 1980s and ’90s against the cigarette company Philip Morris, which funded exhibitions (and a branch of the Whitney), and the 2014 edition of the Biennale of Sydney, from which some artists withdrew after reports revealed that the exhibition’s founder is a funder of migrant detention centers.

“We need to continue to keep an eagle eye on the governance and sponsorship of institutions,” Rosler said in an email. “Can they develop a less oligarchic, more transparent form of governance?”

Artist Hito Steyerl, who earlier this year said that showing at the Sackler-funded Serpentine Galleries in London was “like being married to a serial killer,” agreed with Rosler, saying in an email, “I think this is another step towards an art world that is not tilted towards oligarch power—a step that echoes the unmaking of the Louvre Sackler wing and other examples of institutions to divest from toxic influences on the art world.”

With regard to the Louvre, enough time had passed from the Sackler’s donation that the administration was allowed to remove their name, but in many other cases, cutting ties with controversial funders may be more complicated, whether because of funding needs or legal constraints.

Speaking with the New York Times, the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, said of Kanders, “Here’s a man who has given a tremendous amount of his time and money to young, often edgy and radical artists—somebody who is very progressive—that’s one of the ironies of all this.” The fear among some museum leaders is that the Whitney debacle may hinder fundraising, as potential patrons shy away from giving in an environment of increased scrutiny.

“The world is full of imperfect people who, especially if they’re well-off, have done things that will offend other people,” David Gordon, an adviser who has served as the director the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Milwaukee Art Museum, said. “If a museum is attempting to survive in a mixed economy, it’s going to rely extensively on donations from large donors. Some of these large donors—companies or individuals—will do things that are objectionable to some people.”

Gordon said that this could lead to museums ending up with a loss of funding. “If you become ultra-pure about who you take your money from, you end up diminishing the ability of the museum to be effective in the public arena,” he said, adding, “Mr. Kanders has not done anything illegal. He didn’t fire the tear-gas. He’s in a business that makes tear-gas. Should we take a position that anybody who manufactures things can be used in a way you don’t like be banned from the museum? We should sit down and discuss it.”

As it is, there are no industry standards for such questions. A spokesperson for the Association of Art Museum Directors, which sets down rules and recommendations for how directors should operate their institutions, said that it does not offer guidelines for how leadership should review prospective donors and their business dealings.

Some artists and activists argue that cultural institutions should adopt such rules. The artist Andrea Fraser, who’s spent a career examining and critiquing institutions, said that both museum directors and boards should be proactive in creating standards by which they evaluate potential donations.

“At the very least, this should motivate museum boards to reexamine their board member agreements, bylaws, governance policies, and criteria for board membership,” Fraser said. “They need to ensure that they have language requiring that board members’ activities are consistent with, and should not undermine, the organization’s mission and values, and they need to ensure that they have mechanisms to remove board members who fail to meet that standard. Then they need to have a serious discussion about what those mission and values are.”

“At this point,” Fraser added, “museum directors and board members who don’t initiate this kind of discussion should be considered negligent.”

[ad_2]

Source link